Implementing Network Egress Control in Docker Swarm

Learn how to lock container internet access and route outbound traffic through a controlled forward proxy. Stop compromised containers from reaching the internet.

Docker containers can reach the internet by default. A single compromised service can then download tools, exfiltrate data, or phone home to a command-and-control server. Egress control locks outbound access so that only approved traffic goes through a forward proxy.

This guide focuses on a swarm stack using a forward proxy installed on the host bound to the docker0 bridge IP (e.g. 172.17.0.1), so services can use host.docker.internal:3128 without hardcoding IPs. Non-internal overlay networks and iptables (FORWARD + optional INPUT restrictions) block attempts to bypass HTTP/HTTPS_PROXY and allow direct database access.

Why Egress Control Matters

In a typical production setup, applications need to call external APIs (e.g. GitHub, Stripe, SendGrid), connect to a managed database, and talk to each other. We'll start with how things work by default, then show how to lock them down.

Default: open outbound access

Out of the box, Docker gives every container full outbound access. There is no egress firewall and no requirement to use a proxy. From inside any container:

Every container can reach:

├─ Any website on the internet ✓

├─ Any API endpoint ✓

├─ Any sketchy download site ✓

└─ Any attacker's command server ✓

Legitimate traffic and abuse use the same pipe. If an attacker compromises one container through a dependency, misconfiguration, or any vulnerability, they can:

- Phone home to their command-and-control server

- Download tools for privilege escalation or lateral movement

- Exfiltrate your data to any server they control

- Scan your network for other vulnerable services

Locked down: egress control

With egress control, outbound traffic is restricted. Containers can only reach what you allow: the forward proxy (for approved internet destinations) and specific subnets (e.g. your database). Everything else is dropped.

With egress control, each container can reach:

├─ Forward proxy (host) → proxy decides which domains are allowed ✓

├─ Your database subnet (e.g. 150.200.0.0/20) ✓

├─ Other containers on the overlay ✓

└─ Direct internet, sketchy sites, C2 servers ✗ (blocked)

The rest of this guide walks through how to get from the default (open) setup to this locked-down one: host proxy, iptables rules, and optional INPUT restrictions.

Without it, one compromised container can become a full-blown incident: data exfiltration, lateral movement, and regulatory fallout (SOC 2, PCI DSS, HIPAA). Consider egress control whenever you run production workloads with sensitive data, third-party or untrusted code, or simply want defense in depth. Essentially, you need egress control anywhere a breach would be costly.

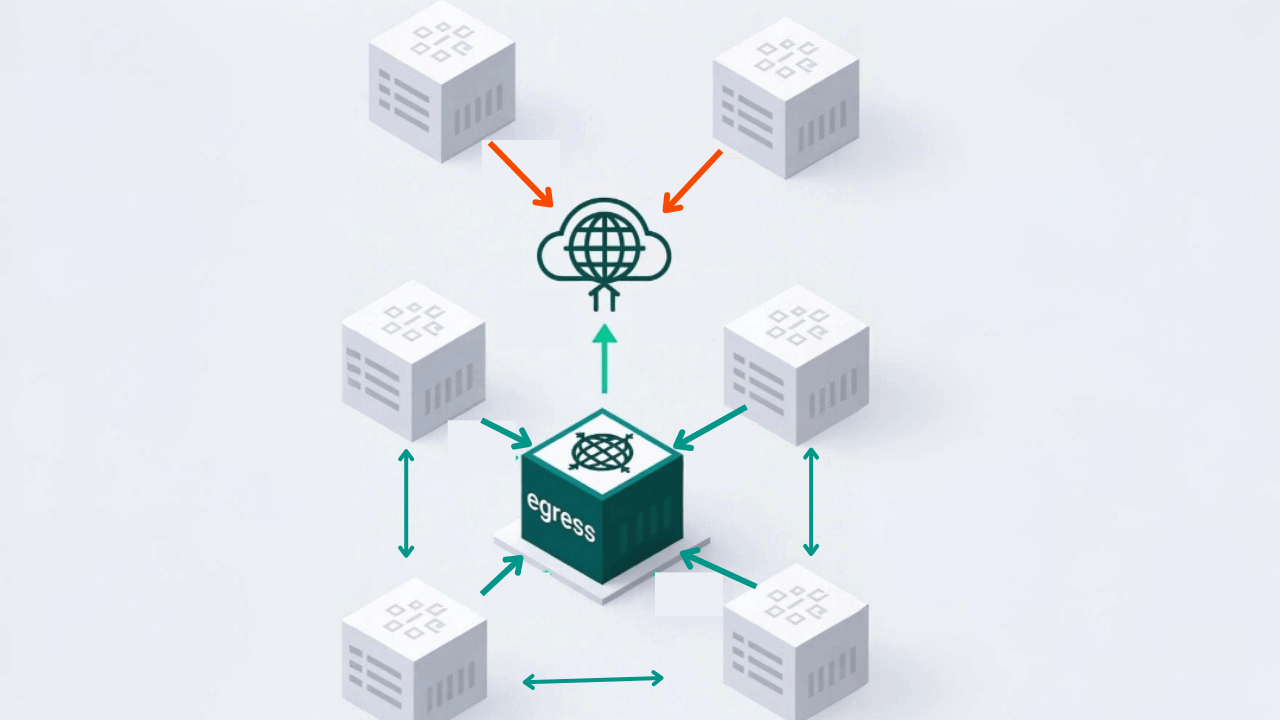

Architecture: Host Proxy + iptables

- Forward proxy runs on the host (e.g. installed directly on the host, or run on Docker with

network_mode: host), bound to the docker0 bridge IP (e.g.172.17.0.1:3128). It is not exposed on the public internet; only the host and Docker networks can reach it. - Swarm services use

host.docker.internal:3128forHTTP_PROXY/HTTPS_PROXY, so you avoid hardcoding the proxy IP across environments. - All overlay networks are non-internal so containers have normal routing and can resolve DNS; no

--internalflag. - iptables FORWARD chain (DOCKER-USER) blocks container traffic to the internet, except traffic to your allowed subnets.

- Database access is allowed through a destination based iptables rule (e.g.

-d 150.200.0.0/20 -j ACCEPT). - Container-to-container traffic stays on the overlay and never hits iptables.

Containers set HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128. Traffic to the proxy goes to the host (INPUT chain). The proxy runs on the host and binds to the docker0 IP, so its outbound traffic uses the OUTPUT chain and is not blocked by FORWARD. Direct container to internet traffic goes through FORWARD and hits the DROP rule. Optionally, an INPUT chain rule can be added to restrict port 3128 to sources from the Docker bridge/gwbridge subnets so only containers (and the host) can reach the proxy.

Why the proxy runs on the host

Your forward proxy can absolutely run in a docker container, but must be bound to the host network. This is the important bit. If it uses docker network, its egress would go through the same FORWARD chain as other containers. You'd need to distinguish "proxy container" traffic from "app container" traffic (e.g. by source IP or network). With the forward proxy on the host network, the proxy’s outbound traffic uses the OUTPUT chain and is not subject to FORWARD. This allows us to set one FORWARD rule to give our pre-approved subnets access, and drop everything else that leaves through the external interface. That same rule set forces all container internet traffic to go through the proxy or fail.

Understanding the network paths

Docker Swarm containers have two network interfaces:

Overlay network — For talking to other containers.

- Container A → Container B: direct, fast, no iptables.

- Never affected by egress controls.

Gateway bridge (gwbridge) — Path to the outside world. All container traffic that leaves the overlay: whether to the host, a database, or the internet goes through the gwbridge.

Three path traffic enforcement

Every packet leaving a container goes through the host. Where it goes next depends on the destination:

Path 1 — Internet through the proxy (allowed)

Container sends to host.docker.internal:3128 → host receives it (INPUT) → forward proxy makes the real request to the internet (OUTPUT). Allowed. The proxy’s ACL decides which domains are permitted.

Path 2 — Internet direct (blocked)

Container sends to e.g. google.com → packet leaves via the host’s external interface → FORWARD chain → DROP rule matches. Blocked. The container cannot bypass the proxy.

Path 3 — Database (allowed)

Container sends to an IP in your DB subnet (e.g. 150.200.0.5) → FORWARD chain → ACCEPT rule for that subnet matches. Allowed. Database traffic never goes through the proxy.

We can use this setup reliably because: (1) containers can reach the host where the proxy lives; (2) containers cannot reach the internet directly (iptables blocks it); (3) the proxy can reach the internet (uses OUTPUT chain, not blocked).

In short: traffic to the host (proxy) and to the database subnet is allowed; all other container egress is dropped.

iptables chain summary

| Traffic | Chain | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Container → internet (direct) | FORWARD | DROP (blocked) |

| Container → database subnet | FORWARD | ACCEPT |

| Container → host proxy (host.docker.internal:3128) | INPUT | Allowed (proxy binds docker0) |

| Host proxy → internet | OUTPUT | Allowed |

| Container → container (overlay) | — | No iptables (overlay only) |

Why not use --internal networks?

Docker's --internal flag creates a network with no external access. Containers cannot reach the internet or any other host outside the overlay. This is fine if your containers never need to reach anything external. If you do need direct access to specific IPs, for example a managed database that does not speak HTTP and cannot use the proxy, --internal is the wrong tool. It blocks all egress, so those connections fail. In many setups external DNS resolution from internal networks is also limited or blocked.

Using non-internal networks + iptables instead gives:

- Granular control — Allow the database subnet, block everything else to the internet.

- Database access — Direct, no proxy overhead; one destination-based rule.

- Same enforcement — FORWARD rules apply to all container egress; the proxy runs on the host (OUTPUT), so it is not blocked.

Forward Proxy Basics

Reverse proxies (e.g. nginx, Traefik, Caddy) sit in front of your services and handle incoming traffic. A forward proxy does the opposite: it sits in front of your apps and handles their outgoing traffic to the internet.

Reverse Proxy: Internet → Proxy → Your Apps

Forward Proxy: Your Apps → Proxy → Internet

How HTTP Proxying Actually Works

When you set HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128 in your container's environment:

For regular HTTP requests:

- Your app sends:

GET http://api.example.com/data HTTP/1.1to the proxy - The proxy makes the request to example.com on your app's behalf

- The proxy returns the response to your app

For HTTPS requests (the more interesting case):

- Your app sends:

CONNECT api.example.com:443 HTTP/1.1to the proxy - The proxy establishes a TCP tunnel to example.com:443

- The proxy responds:

HTTP/1.1 200 Connection Established - Your app does a TLS handshake directly with example.com through the tunnel

- The encrypted traffic flows through the proxy (which can't read it)

The proxy sees the destination hostname (from the CONNECT request) but not the encrypted body. So domain-based allowlists work: the proxy can allow or deny api.github.com without inspecting the TLS payload.

Setting Up Caddy on the Host

As mentioned earlier, you can instal your forward proxy directly on the host machine or run in docker container using rhe host network (e.g. network_mode: host). The proxy needs to binds only to the docker0 bridge IP (typically 172.17.0.1). That way the proxy is reachable by containers via host.docker.internal. In our example, we use a caddy image build that includes the forward_proxy plugin (e.g. via xcaddy).

Minimal Caddyfile — bind to the docker0 IP (set via Ansible or env; default 172.17.0.1):

:3128 {

bind 172.17.0.1

forward_proxy {

ports 80 443

acl {

allow *.github.com

allow api.stripe.com

allow *.sendgrid.net

allow ifconfig.me

deny all

}

}

}

Docker Compose — run Caddy with host networking so it can bind to the host's docker0 IP:

services:

caddy-egress:

image: your-caddy-egress:forwardproxy # build with forward_proxy plugin

network_mode: host

volumes:

- ./Caddyfile:/etc/caddy/Caddyfile

restart: alwaysBreaking this down:

bind 172.17.0.1— Caddy listens only on the docker0 interface. This does not expose your proxy server port on the public IP; containers reach it viahost.docker.internal:3128. You can template the bind address (e.g. from Ansibleansible_docker0.ipv4.address) so it works across hosts.

Note on host.docker.internal: This hostname is available by default in Docker Desktop. On Linux servers, add it via extra_hosts so containers can resolve it:

services:

web-app:

extra_hosts:

- 'host.docker.internal:host-gateway'

environment:

- HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128

- HTTPS_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128Alternatively, use the docker0 IP directly (e.g. 172.17.0.1:3128).

ports 80 443— Only proxy HTTP and HTTPS traffic. This prevents abuse as a generic TCP tunnel.acl— Your allowlist. Apps can only reach explicitly permitted domains.deny all— Everything not explicitly allowed is blocked.

Traffic Flows in This Setup

These are the main traffic patterns and how they behave.

Scenario 1: App Tries to Reach Internet Directly (Blocked)

1. App container tries: curl https://google.com (no proxy)

2. Container uses gateway bridge (gwbridge)

- Source IP: 172.18.x.x (container's gwbridge IP)

- Destination: google.com

3. Packet enters host's FORWARD chain

- DOCKER-USER rules run first

- ESTABLISHED,RELATED: no match (new connection)

- -d 150.200.0.0/20: no match (destination is internet)

- -o eth0 -j DROP: matches ✓

4. Packet dropped. Connection fails (timeout or connection refused).

iptables enforces proxy usage: any container traffic leaving via the external interface (other than to the database subnet) is dropped.

Scenario 2: App Reaches Internet Through Proxy (Success)

1. App has environment variables set:

HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128

HTTPS_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128

2. App tries: curl https://api.github.com

3. host.docker.internal resolves to the host; app connects to port 3128

- Traffic goes: container → host (INPUT chain)

- Caddy is bound to docker0 (e.g. 172.17.0.1:3128), so it receives the connection

4. Caddy (on host) receives: "CONNECT api.github.com:443"

- Checks ACL: *.github.com allowed ✓

5. Caddy opens outbound connection to api.github.com

- Uses OUTPUT chain (host traffic)

- Not affected by DOCKER-USER FORWARD rules ✓

6. Caddy tunnels TLS between app and GitHub

- App ↔ Host proxy ↔ GitHub

- Encrypted end-to-end

The app gets its data only through the proxy, so the allowlist is enforced. Bypass attempts are blocked by the DROP rule.

Scenario 3: Container-to-Container Communication (Always Direct)

1. App tries: curl http://another-swarm-service:8080

2. Docker DNS resolves another-swarm-service → overlay IP (e.g. 10.0.48.5)

3. Destination is on overlay; traffic stays on overlay

- Same host: overlay bridge, microseconds

- Different host: VXLAN (UDP 4789), 1–2 ms

4. Never touches gwbridge, never touches iptables ✓

Overlay traffic is unaffected by the FORWARD rules. Microservices on the same overlay communicate as usual.

Scenario 4: Accessing a Private Database

Forward proxies handle HTTP/HTTPS. Database clients use their own wire protocol (e.g. PostgreSQL), not HTTP, so they cannot use the proxy. Database traffic must go directly to the DB. An iptables rule allows that.

# Allow traffic to your managed database subnet (adjust to your VPC)

iptables -I DOCKER-USER 1 -m conntrack --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

iptables -A DOCKER-USER -d 150.200.0.0/20 -j ACCEPT

iptables -A DOCKER-USER -o eth0 -j DROPFlow:

1. App tries: psql -h db-host.db.db-domain.com

2. DNS resolves to an IP in 150.200.0.0/20

- Traffic leaves container via gwbridge

- Enters FORWARD chain

3. DOCKER-USER: -d 150.200.0.0/20 -j ACCEPT matches ✓

- Packet accepted, forwarded to database

Using NO_PROXY

With HTTP_PROXY and HTTPS_PROXY set to http://host.docker.internal:3128, many apps send all HTTP/HTTPS traffic through the proxy. Internal service-to-service calls should bypass it to avoid extra latency. Use NO_PROXY for that:

HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128

HTTPS_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128

NO_PROXY=127.0.0.1,internal-api,service-aInternal hostnames (e.g. internal-api, service-a) then connect directly over the overlay; only external services should go through the proxy. This keeps internal traffic fast, and you do not need to add your internal hostnames to the proxy's ACL.

Troubleshooting

"Apps can't reach the internet (even with proxy)"

- Check Caddy: Is it running and listening on the docker0 IP?

ss -tlnp | grep 3128(should show e.g.172.17.0.1:3128). - Check env: Containers must have

HTTP_PROXY=http://host.docker.internal:3128(or the host's docker0 IP). Ensurehost.docker.internalresolves (Docker Desktop sets it; on Linux you may need to add it toextra_hostsor use the gateway IP). - Check ACL: Is the domain in the Caddyfile

aclallowlist?

"Containers can reach the internet without using the proxy"

- Check DROP rule:

sudo iptables -L DOCKER-USER -n -v. You should see a rule like-o eth0 -j DROP. - Check interface: If your external interface is not

eth0, the DROP rule must use the correct-o <interface>. - Check order: ESTABLISHED/RELATED and database ACCEPT rules should come before the DROP rule.

"Database connection fails"

- Check iptables:

sudo iptables -L DOCKER-USER -n -v. There must be an ACCEPT rule for your database subnet (e.g.-d 150.200.0.0/20). - Check subnet: Confirm the DB's actual IP is in that subnet (e.g.

nslookup db-host.db.db-domain.com). - Check DB firewall: The database provider must allow connections from your nodes.

"Container-to-container broken"

Overlay traffic does not go through iptables. If internal communication fails, check that both services are on the same overlay network (docker inspect <container> --format '{{json .NetworkSettings.Networks}}').

"Rules gone after reboot"

DOCKER-USER is not always persisted. Use netfilter-persistent (and save after adding rules) or a systemd unit / script that reapplies the rules after Docker starts.

Subnet overlap

If your Docker overlay subnet overlaps with your VPC/database subnet, routing can be wrong (e.g. container thinks DB is on overlay). Use non-overlapping ranges; see CIDR guide.

What This Protects (and What It Doesn't)

What it defends against

- Compromised containers phoning home — Can't reach arbitrary C2; only allowlisted domains.

- Data exfiltration — Can't POST to attacker-controlled servers; only approved APIs.

- Tool downloads — Can't wget/curl from arbitrary sites; direct egress is dropped.

- Supply chain — Malicious deps can't reach out except via proxy allowlist.

What it doesn't protect against

- Abuse of approved domains — e.g. hosting payloads on an allowed domain like GitHub.

- Exfil via approved APIs — Attacker could POST data to allowed endpoints; monitor logs.

- Container-to-container — Overlay is unrestricted; use service auth.

- Non-network attacks — Privilege escalation, resource exhaustion, app logic flaws.

This is one layer in defense-in-depth. You still need updates, scanning, monitoring, and incident response.

Performance Impact

- Container-to-container: No change; overlay only.

- External HTTP/HTTPS: One extra hop to the host proxy; typically a few ms; often dominated by external API latency.

- Database: Direct via iptables exception; no proxy involved.

Conclusion

Egress control in this setup is: Caddy on the host bound to the docker0 bridge IP (e.g. 172.17.0.1:3128) + non-internal overlay + iptables DOCKER-USER (allow database subnet, drop rest via external interface). Services use host.docker.internal:3128 so you don't hardcode the proxy IP. The proxy enforces a domain allowlist; database traffic is allowed by a destination-based iptables rule.

A full example can be found on my Egress Playground.